June 2024 Newsletter

June 2024 Newsletter

In this month's newsletter: The New Money is Needed to Pay Off Old Debt Fallacy. See below or view the article in your browser.

Dear Readers,

The European Central Bank, (ECB), decided to screw the people of the Eurozone on Thursday by loosening monetary policy despite their ongoing suffering from high prices and rising inflation in May. We didn’t need more proof that these evil institutions need shutting down, but we got it anyway.

So the wealth transfer from earners and savers to leveraged speculators continues until the people say they’ve had enough and demand sound money.

However, there are those that believe (or at least claim to believe) the money supply has to keep expanding to pay back existing debt, and this justifies central bank looting. Whenever you hear such statements, I think it is important to pick them apart to see if they are actually true, which I do here.

The New Money is Needed to Pay Off Old Debt Fallacy

You often hear it said by those who claim expertise in finance and banking that, in a debt-based fiat system, new money must be created to settle existing debt. The motivation for it being that it justifies endless money supply expansion and currency debasement.

But is it true, and how can it be proven either way? To cut a long story short, the answer is no, it is not true, and, if you want proof, it can be proven through a simple double-entry accounting example.

Analysis

Imagine Alice, the first ever banker, sets up the first ever bank, and lends Bob, a candlestick maker, £10 at 10% interest, to be paid back in 5 instalments of £2.20. In total, Bob will have to pay back £11.

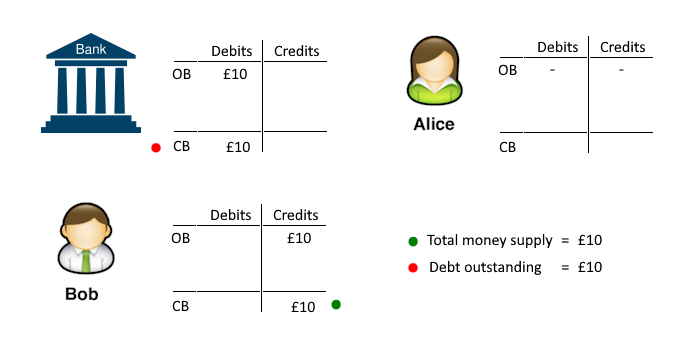

First, Alice creates the fiat money for Bob at her bank as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Double entries* for a £10 loan issued at Alice's bank for Bob.

* OB = Opening Balance. CB = Closing Balance.

After, the loan creation, the money supply is exactly £10, as expected. For simplicity, Bob doesn't spend the money but just pays it back. The outcome would not be any different if he did, as will be clearer by the end.

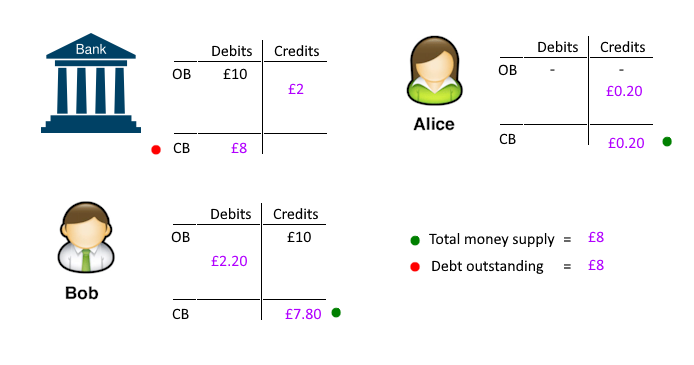

Hence, the next double entry is for Bob's first 1st instalment of the loan. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Double entries for Bob's 1st instalment of the loan.

After the 1st instalment, the money supply is reduced by £2 and is now £8. So why is the money supply not reduced by the £2.20 paid back? Because interest is earnings, and this goes to the bank's profits, or more precisely the bank's owners, i.e., to Alice. It remains in the money supply, and this is the key (although we aren't completely out of the woods yet, as you will see).

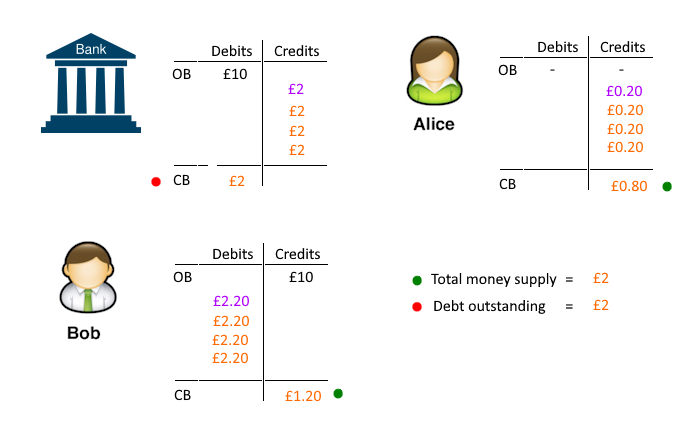

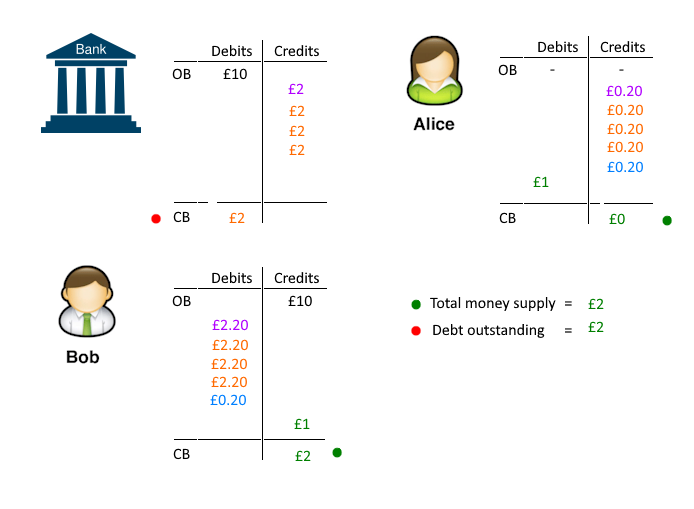

After 3 more loan instalments, the money supply has shrunk to £2, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Double entries for 3 more instalments.

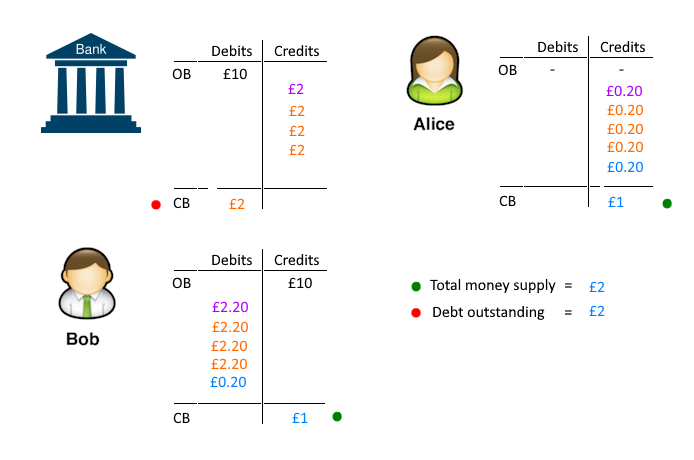

But Bob has a slight problem now in that he does not have enough funds to pay the last instalment. He only has £1.20 whereas he needs £2.20. But he can pay the interest due, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Double entries for interest on the final instalment of the loan.

But what does it actually mean for Alice to have £1 of money her bank created? Alice can spend it of course, but on what? There needs to be a demand for the money. Someone must be willing to accept the money in exchange for good and services. The only person in town is, of course, Bob. So Alice happily purchases a candlestick from Bob for £1 as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Double entries for Alice's purchase of a candlestick from Bob for £1.

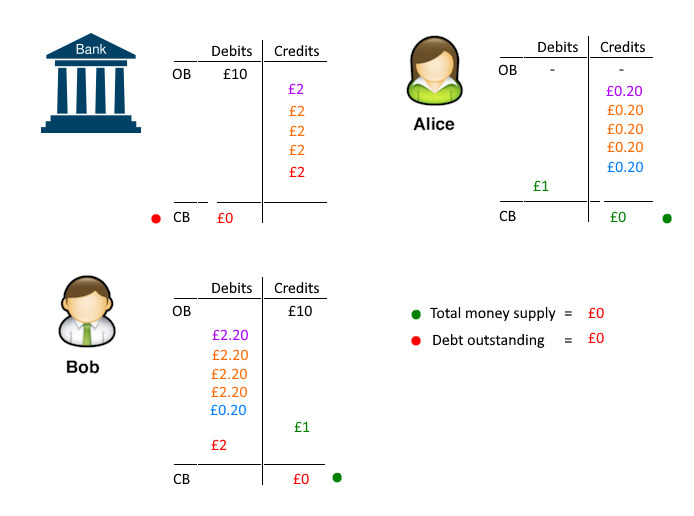

And now Bob has sufficient funds to pay off the remaining £2 owed, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Double entries for Bob's repayment of the remaining £2 owed.

After the loan is fully paid back, there is no money in circulation and no debt outstanding. No additional money had to be created for Bob to pay back the loan.

Conclusions

This simple example shows that there is always sufficient money in a debt-based fiat system to pay off existing debt. In total, Bob paid back £11, whilst the money supply never exceeded £10—the initial amount created.

The fact that Bob may not have had sufficient funds in his account at all times is neither here nor there because there was still enough money in the system. And, just like in the real world, Bob had to work and exchange his produce for that money.

It may have been 'easier' for Bob if new money had been created, but it wasn't necessary. Quantitative 'Easing' (QE) is where central banks (CBs) effectively do this by artificially increasing supply—effectively counterfeiting.

Regardless of whether the money supply expands, shrinks or remains static, there is always enough money in the system to pay back bank loans.

Discussion

The key take from this analysis is that only the principal of a bank loan is created and destroyed in the banking system. Interest is the price paid for a service, and just as when you pay for a service, money doesn't just disappear; it just changes hands.

On a related note, this is why CBs remit interest payments on bonds back to their governments. Otherwise, in theory, if a CB entered both QT (Quantitative Tightening or reverse QE) and interest payments on its balance sheet, its balance sheet could go negative. Only losses would prevent it from doing so, but this is a subject for a different article.

To comment or discuss the content of this article, please reply to my Twitter/X post containing the link to this article, or email me.