April 2024 Newsletter

April 2024 Newsletter

In this month's newsletter: The Bank Tokens Analogy is Wrong. See below or view the article in your browser.

Update

It's taken me a while to do a newsletter, mainly because I've been active on Twitter with the time I have available. My plan is to aim for a monthly newsletter covering topics relating to money, even if it is just a short one, and to add more content to my website.

Markets

Bitcoin reached an all-time high in March, gold is currently making all-time highs with silver hot on its heels, and the S&P 500 also made all-time highs in March. It's almost as if there is a bit of a melt up going on.

But how can this be when the global economy seems to be in the gutter, and zombies are starting to roam the financial landscape? It's not as if central banks create money when they mark up those digits in banks' bank accounts is it? It's not like Q.E. was the reason UK house prices correlated almost perfectly with the increase in the money supply from 2009?

Actually, it is because of that, as most of you know.

But central bank reserves aren't money are they? They are really just bank tokens only used by banks. Well, yes they are money, and no, they aren't bank tokens. Here's why.

The Bank Tokens Analogy is Wrong

Those that follow me on Twitter/X will know I'm not a fan of unsound fiat money—money governments can debase. But nor am I a fan of unsound analogies about money and banking.

In this article, I’m going to address the ‘electronic bank tokens’ analogy, using the favourite tool of proponents of it: double-entry accounting. The analogy is primarily used to try to show central banks don't create money when they carry out quantitative easing or lend to banks.

Analysis

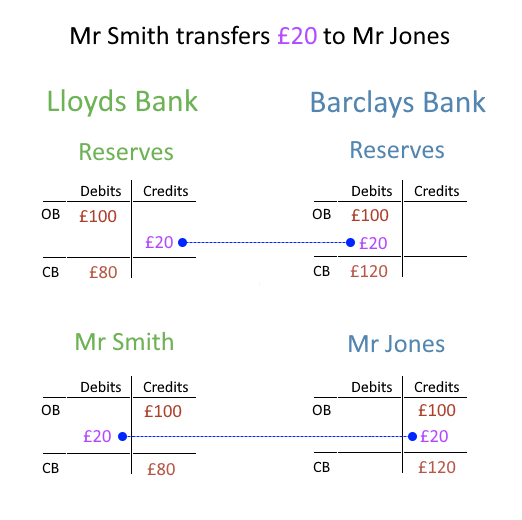

Imagine Mr Smith, who banks with Lloyds Bank, transfers £20 to Mr Jones, who banks with Barclays Bank. According to the 'tokenists', this can be represented by the accounting entries shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Two double entries representing a bank transfer*.

* Opening balances (OBs) are all £100 for simplicity, but could be anything of course.

The bottom double-entry transfers deposit tokens (liabilities between banks) and the top transfers reserve tokens (assets between banks). Reserve and deposit tokens are never mixed since they are of different ‘types’.

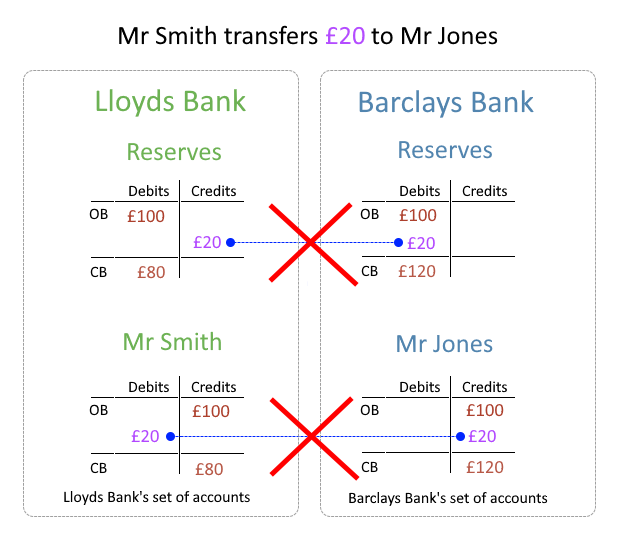

But there is a glaring hole in the accounting, as anyone who understands double-entry bookkeeping will spot straight away. This is that the double entries are across different sets of accounts, which is wrong, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. These accounting double entries are wrong.

In double-entry accounting, which all banks use, every credit must have a corresponding debit (or debits totalling the credit), and vice versa, within a set of accounts. Both Lloyds’ and Barclays’ sets of accounts would break this rule.

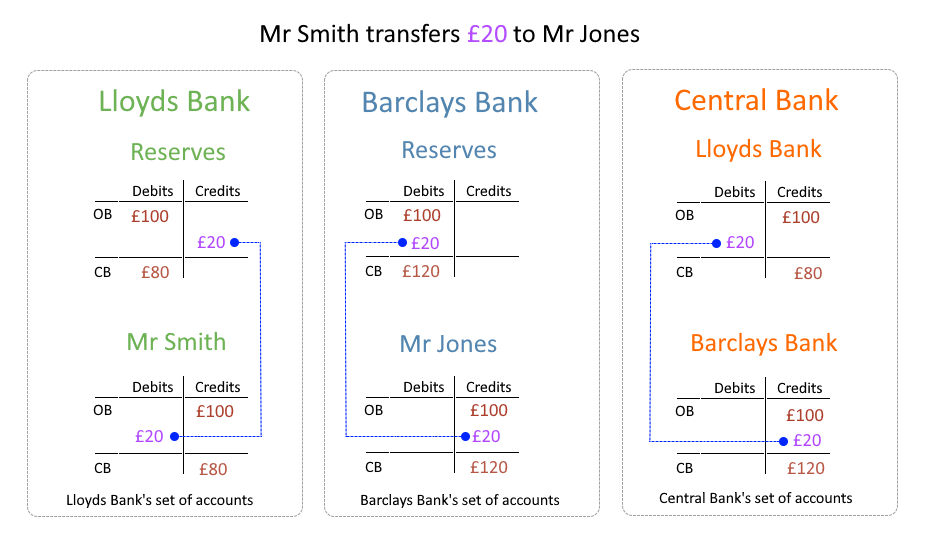

The correct double entries are shown below in Figure 3.

Figure 3. These are the correct accounting double entries.

These are the double entries that banks coordinate between each other for the transfer, including the central bank. If something goes wrong, the entries can be reversed. There is no situation in which any set of accounts can be unbalanced, and settlement can still take place at a later time if necessary.

Conclusions

When someone transfers their money via a bank transfer, money, not tokens, is transferred. Customer deposit accounts are accounts of money, not tokens, as are central bank reserve accounts. Cash can be withdrawn on either if required, and money is interchangeable between these accounts because it is the same money.

Discussion

To comment or discuss the content of this article, please reply to my Twitter/X post containing the link to this article, or email me.